JavaScript - Closure in depth

November 21, 2019 - 8 min read

In this article we will learn about the concept of closures in JavaScript, we will see how functions can be stateful with persistent data across multiple executions. We will also explore some of the popular use cases of closure and different approaches for using them.

Lets start with a quote from MDN:

A closure is the combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function. In JavaScript, closures are created every time a function is created, at function creation time.

If you ask me, i would say that closures enables us to create stateful functions.

Stateful functions

Stateful functions are functions that can “remember” data from previous executions. For example lets create a function that “remembers” and count how many times it got executed, each time that we will invoke it, it will log the number of times it got executed.

To do that, we will need some kind of a counter variable that will hold the current number of executions and will get incremented every time we invoke the function, the challenge here is to decide on where to put this variable.

Lets explore our first approach:

function counter(){

let numOfExecutions = 0;

numOfExecutions++;

console.log(numOfExecutions);

}

counter() // 1

counter() // 1Obviously this won’t work well, because we are re-creating the numOfExecutions variable every time we invoke counter().

Execution context

Every time we invoke a function, a new execution context is created, and each execution context has it’s own “Variable Environment” or “scope” if you will. This local variable environment is holding all arguments that got passed to it and all declarations made inside the body of the function, in our case the numOfExecutions variable. When the function is “done”, e.g with a return statement or there are no more lines of code to execute, the engine will mark it to be garbage collected, meaning it’s entire environment will get disposed.

This is the reason our code above doesn’t work well, every time we invoke counter we create a new execution context with a new declaration of the numOfExecutions variable and incrementing it to the value of 1.

Global execution context

When we start our program, the engine will create a global execution context for us, its not different from the execution context we create when we invoke a function. It also has a “Variable Environment” just like any other execution context, the difference is that the global execution context will never “die” (as long as our program is running of course), hence it’s variable environment won’t get disposed by the garbage collector.

So knowing that, we can maybe store our numOfExecutions in the global variable environment, this way we know it won’t get re-created each time we invoke counter.

let numOfExecutions = 0;

function counter(){

numOfExecutions++;

console.log(numOfExecutions);

}

counter() // 1

counter() // 2This works as we expect, we get the correct number of invocations, but you probably already know that storing variables on the global environment is considered as bad practice. For example see what happens if another function wants to use the exact same variable:

let numOfExecutions = 0;

function counter() {

numOfExecutions++;

console.log(numOfExecutions);

}

function someFunc() {

numOfExecutions = 100;}

someFunc()

counter() // 101

counter() // 102As you can see we get some wrong numbers in here.

Another issue with this approach is that we can’t run more than 1 instance of counter.

Lexical Scope

Lexical Scope is basically a fancy way of saying “Static Scope”, meaning we know at creation time what is the scope of our function.

Read this carefully:

WHERE you define your function, determines what variables the function have access to WHEN it gets called.

In other words, it doesn’t matter where and how you invoke the function, its all about where did it got declared.

But how do we declare a function in one place, and invoke it in another place? Well, we can create a function within a function and return it:

function createFunc() {

function newFunc(){

}

return newFunc;

}

const myFunc = createFunc();

myFunc()It may seem useless, but lets explore the execution phase of our program:

- We declare a new function with the

createFunclabel in the global variable environment. - We declare a new variable

myFuncin the global variable environment which it’s value will be the returned value from the execution ofcreateFunc. - We invoke the

createFuncfunction. - A new execution context is created (with a local variable environment).

- We declare a function and giving it a label of

newFunc(stored in the local variable environment ofcreateFunc). - We return

newFunc. - The returned value from

createFuncis stored as the value ofmyFuncin the global variable environment. - The variable environment of

createFuncis marked for disposal (meaning thenewFuncvariable will not exist). - We invoke

myFunc.

Note that when we return the function newFunc, we return the actual function definition, not the label.

OK, so what can we do with this approach?

It turns out, that when we return a function, we are not only returning our function definition but we also return it’s entire lexical environment. I.e, if we had some variable declared in the same context (or outer contexts), our returned function would close over them, and keep a reference to them.

Lets see that in action with our counter example:

function createCounter() {

// creating a wrapping execution context

// so we won't pollute the global environment

let numOfExecutions = 0;

// creating and returning an inner function

// that closes over the lexical environment

function counter() {

numOfExecutions++;

console.log(numOfExecutions);

}

return counter;

}

const counter = createCounter();

counter() // 1

counter() // 2As you can see, we are creating a wrapper execution context (createCounter) to store our numOfExecutions variable and we are returning the counter function. This way, every time we invoke counter it has access to the numOfExecutions variable. The fact that we are not re-running createCounter and only run counter let us persist numOfExecutions across executions of counter, thus allow counter to be stateful, meaning we can share data with multiple executions of this function.

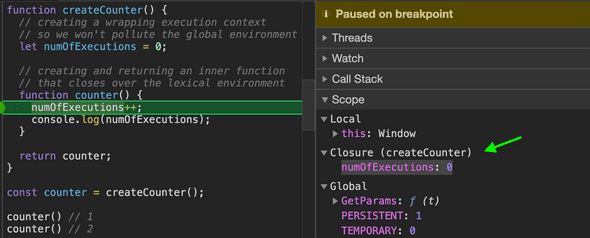

If we debug counter’s execution we can see in the developer-tools that numOfExecutions is not stored in the local variable environment of counter but in it’s “Closure” scope, (refers to as [[Scope]] in the spec).

But what if we wanted to return an object and not a function?

No problem, it will still work as expected:

function createCounter() {

let count = 0;

function increment() {

count++;

return count;

}

function decrement() {

count--;

return count;

}

function reset() {

count = 0;

}

function log() {

console.log(count)

}

const counterObj = {

increment,

decrement,

reset,

log

}

return counterObj;

}

const counter = createCounter();

counter.increment()

counter.increment()

counter.increment()

counter.log() // 3☝️ By the way, this pattern is usually called the “Module Pattern”.

As you can see, it doesn’t matter what we are returning, it doesn’t matter where or when we are calling the functions, the only thing matters is where did we defined our functions:

WHERE you define your function, determines what variables the function have access to WHEN it gets called.

Another bonus we get from returning a function or an object with functions is that we can create multiple instances of counter, each will be stateful and share data across executions but won’t conflict between other instances:

function createCounter() {

let numOfExecutions = 0;

function counter() {

numOfExecutions++;

console.log(numOfExecutions);

}

return counter;

}

const counter1 = createCounter();

const counter2 = createCounter();

counter1() // 1

counter1() // 2

counter2() // 1

counter2() // 2As you can see, counter1 and counter2 are both stateful but are not conflicting with each others data, something we couldn’t do with a global variable.

Optimizations

Every returned function is closing over the ENTIRE lexical scope, meaning the entire lexical scope won’t be garbage collected 🤔. This seems like a waste of memory and even a potential memory leak bug, should we re-consider the use of closures every time we need staeful functions?

Well, no. Most if not all browsers are optimizing this mechanism, meaning that in most cases only the variables that your function is actually using will be attached to the function’s [[scope]]. Why in most cases and not all cases? Because in some cases the browser is unable to determine what variables the function is using, such as in case of using eval. Obviously this is the smallest concern of using eval, it is safer to use Function constructor instead.

Wrapping up

We learned about how “Closure” works under the hood, with a link to the surrounding lexical context. We saw that scope wise, it doesn’t matter when or where we are running our functions but where we are defining them, in other words: Lexical (static) binding. When we return a function, we actually returning not only the function but attach to it the entire lexical variable environment of all surrounding contexts (which browsers optimize and attach only referenced variables). This gives us the ability to create stateful functions with shared data across executions, it also allows us to create “private” variables that our global execution context doesn’t have access to.

Hope you found this article helpful, if you have something to add or any suggestions or feedbacks I would love to hear about them, you can tweet or DM me @sag1v. 🤓